Chris Padilla/Blog

My passion project! Posts spanning music, art, software, books, and more. Equal parts journal, sketchbook, mixtape, dev diary, and commonplace book.

- Earlier this year, after using inline suggestions for some time, the jump to prompting an agent that then writes multiple files' worth of code was shocking! The feeling of it running away conjured images from the Sorcerer's Apprentice.

- Returning to the approach several months later, trying it in my own projects, the results were suddenly thrilling! With the right wrangling, what was previously tedious to implement became trivial. The possibility of accelerated speed was intoxicating.

- The Music of Raymond Scott, composer of the tune Powerhouse, of Warner Bros. cartoons fame.

- Pink Champagne: A Collection of Vintage Light Music, perhaps our closest replacement for the Ren & Stimpy Production Music collection.

- Music To Knit By, humorously reminding me that the themed music streaming playlists are part of a long tradition of pragmatically curated music. Another era's Lofi Hop Hop Beats To Relax/Study To!

- Music by Candlelight at Teogra, classical guitarist & violinist provide easy listening to diners of the titular restaurant, recorded for your listening pleasure.

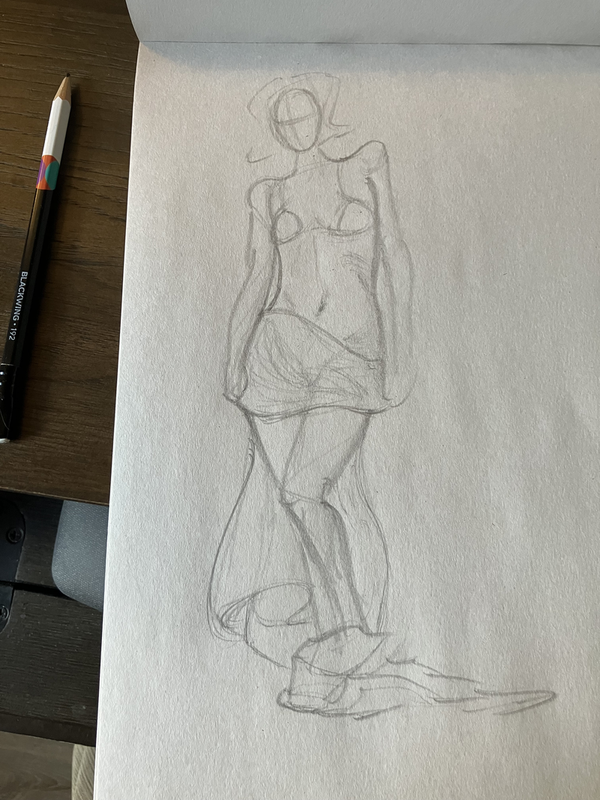

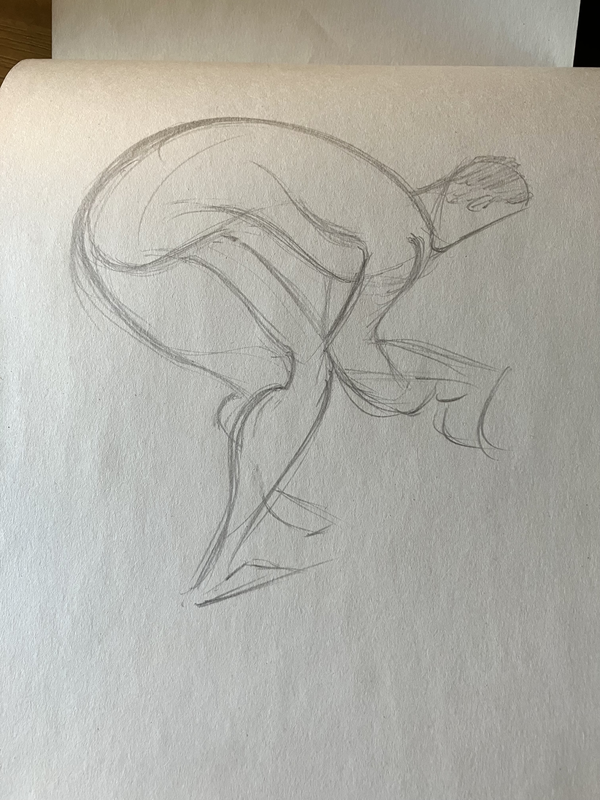

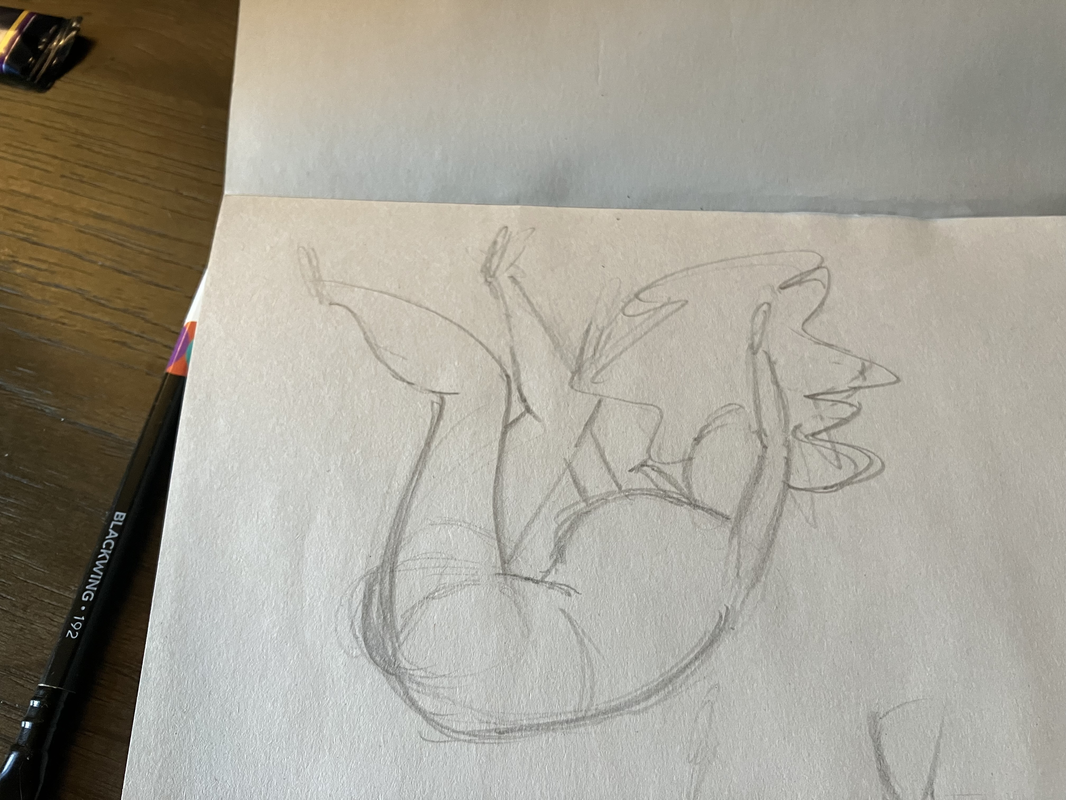

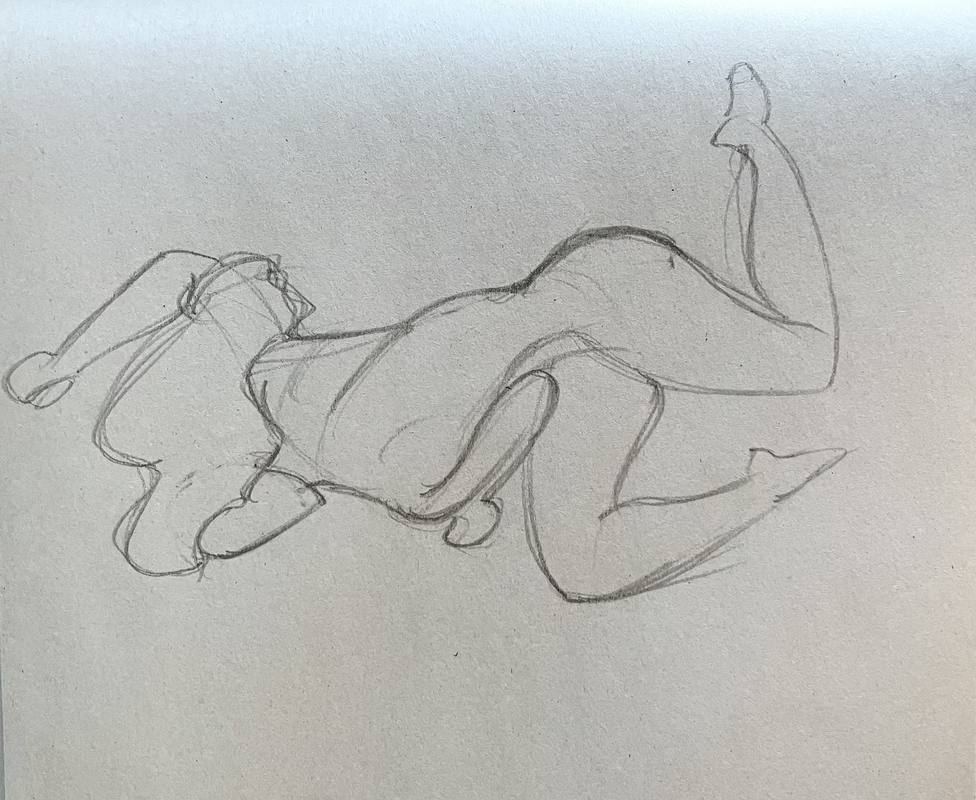

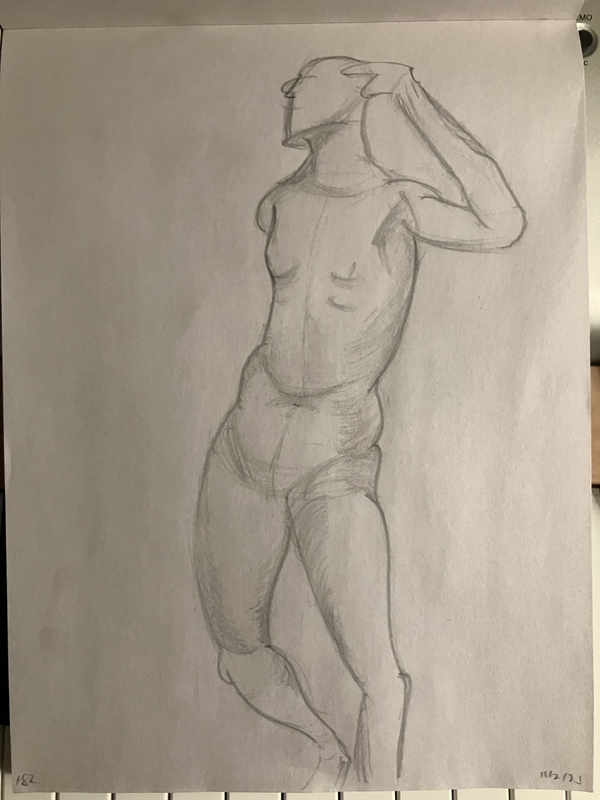

- Get back to pencil-and-paper after a deep dive into fully digital

- Lean into figure drawing

- Don't follow the "just keep going!" approach of sight reading. No need to practice with a metronome early on; you'll learn more from slowly, but successfully playing the correct notes.

- When sight-reading, avoid looking at your hands when you've read ahead a few bars. This is robbing you of the chance to develop proprioception for when you'll need it with denser music.

- Treat it like learning a language. Tackle pieces that you are 80% familiar with the patterns, or as he puts it, that you can play at half speed. Then, don't worry about perfecting every piece. Better to read more pieces quickly than to develop rote muscle memory for the particular piece you are learning.

Claude Code Sound Effects

A riff on Claude Code Muzak. Using the same hooks interface to play a system sound on task completion and when asking a follow-up question. Simply add this to your .claude/settings.json:

{

"hooks": {

"Stop": [

{

"hooks": [

{

"type": "command",

"command": "afplay /System/Library/Sounds/Hero.aiff"

}

]

}

],

"PermissionRequest": [

{

"hooks": [

{

"type": "command",

"command": "afplay /System/Library/Sounds/Funk.aiff"

}

]

}

]

},

}🔔

Critical Thinking and Coding Agents

I've gone the Agentic-AI coding way for the past couple of months. My initial responses to it may mirror your own:

Depending on your bent towards pessimism and optimism, the order of events may be different for you. Programmers, as those who now largely work with AI closely in our daily work, have been getting a very pragmatic understanding of the tool as it's emerging, finding its edges and where it can improve our work. So, naturally, consensus is between the two extremes of rejection and hype. This is a powerful tool, and it takes a separate skill to fully understand where it's appropriate to use and how to get the results you're looking for. Here are some thoughts on navigating the middle path:

Vibe Coding Vs. AI Assisted Coding

It's worth knowing the difference. Similar to how there is a spectrum between scenarios where you are comfortable using a package and scenarios where your team develops your own solution for a problem, there's a range between letting the coding agent have free rein and integrating with that process heavily.

Birgitta Böckeler has a great exploration outlining formally what is really an intuitive process. Prototypes, proof-of-concept, and throw-away code are an easy choice for letting the agent take the wheel. Anything beyond that takes a consideration of the tradeoffs between speed, quality, and cost. (Cost, interestingly, is spread across a few different currencies here: Cost of context in your agent, cost of mental resources you have available, cost of digging through the docs, etc.) For most daily work, debugging and producing production-level code, you'll learn best how to integrate it as part of your process instead of a replacement.

Engaging Critical Thinking

While still in the early days of mass access to integrated LLM usage, we're seeing that the tool is overly eager to be useful. Responses to user queries from the major AI players are long-winded. Coding agents aim for verbose solutions. And speed is the preferred default over what we're now seeing in "reasoning" or "thinking" modes.

The speed and length are somewhat alluring. While getting familiar with these tools, it's easy to pass over much of the reasoning to the tool, but we have to be careful there.

There are a few studies already underscoring the hypothesis that we are thinking less when using these AI tools. You can find them in Maggie Appleton's A Treatise on AI Chatbots Undermining the Enlightenment. There you'll also find a compelling solution to this issue through your own prompt engineering. If the AI tool tends towards flattery and confirmation, tell it to do otherwise.

So our aim is clearly for deep involvement in the process while using these tools, but we have to be mindful that the tool itself may not be working in that interest out of the box. Restraint, practice, and perhaps a different framework of interacting with the agents are required.

The Chat Interface

I think this is also partly due to the UI here.

Agents, be they general-user-facing or, now, IDE integrations, are engaged with through a chat interface. Think of where else this interface exists: Discord, Slack, your favorite social media's direct messages, sms text clients, those finicky chat bubbles on portfolio websites, and, for old-time's sake, AOL Instant Messenger.

You get the idea — these are not interfaces for writing prose, editing and refining a document, and going at a steady pace. This is a space for quick responses and moving the conversation forward. Even the ping-pong of question and answer implies that we should move on with haste.

For a technology whose domain language is... language! It certainly is intuitive. However, for software development in particular, we need to ensure the tool is not so over-eager to spin out the solution that we are then racing to keep up. A thoughtful UI can help encourage this.

Superpowers and Spec Driven Development

Much of this is to say that my sweet spot for AI-assisted coding has been with the aid of a couple of different tools that help mitigate the major concerns above.

For a broad exploration of what's out there in the Spec Driven Development space, Birgitta Bockeler returns with a thoughtful article here.

My favorite at the time of writing has been Superpowers by Jesse Vincent. The technology underneath this is not overly complex: The heart of it is a series of prompts that you can read on the GitHub page.

The framework encourages you to work in phases: First, brainstorming high-level considerations and edge cases, then writing an implementation plan with code samples, and then implementing the plan sequentially with quality checks along the way. A massive improvement in thoroughness from even Claude Code's planning mode alone.

Even better is that markdown files are generated as artifacts along the way. This serves a couple of different purposes: You can limit the context provided to an agent, externalizing it from the current agent's memory and allowing you to spin up another agent to handle the next phase. And, from a user standpoint, we then have the opportunity to step away from the chat interface and thoroughly review the plan thoughtfully.

As an aside — the markdown files are, largely, disposable. Perhaps part of the idea of having these files written is that they can then serve as reference documentation down the line. Unfortunately, change happens quickly, and it then becomes an issue of keeping multiple documents in sync. So, thus far, I've tossed these files after a given phase of a feature is complete.

The primary benefit in my own use is that any feature of medium complexity is now something that I have the chance to think through thoroughly, from high-level design to implementation details, all while also appreciating the benefit of a tool that can type much faster than I can.

Raising Our Gaze

We are still in the wild west. Practices are continuing to evolve. For medium-sized features, Superpowers, along with similar frameworks, are aiding in ensuring that we are using the tools and not the other way around.

Our role is to continue to be the primary holder of context: Only you fully understand the full logistical needs of the project, what sort of tradeoffs you want to make, and the long-term infrastructure work that will keep your application continually extendable.

With that intent in mind, I optimistically see a novel way of development emerging. Another layer of abstraction is being built, where we can continue to move our gaze a bit further from syntax and tedium, and focus on the design aspects of our work that truly matter.

Elephant Gym – Finger

AI Agent Elevator Music

Matt Webb shares via Interconnected Mike Davidson's Claude Muzak:

I suggested last week that Claude Code needs elevator music…

Like, in the 3 minutes while you’re waiting for your coding agent to write your code, and meanwhile you’re gazing out the window and contemplating the mysteries of life, or your gas bill, maybe some gentle muzak could pass the time?

Delightful.

A few tracks are already provided, you'll have to bring your own audio files for more varied listening. Music For Local Forecast. Or perhaps anything Vaporwave! And all sorts of library music comes to mind.

For more whimsy, 1950's era incidental music would also be a terrific fit. Eons ago in internet years, there was a great collection of public domain light music tracks that were used for Ren & Stimpy, but download links are no longer handy.

A few finds from the internet archive that should fit the bill:

As a technical aside, this is a very slick use of Claude Code hooks. Common productive examples could be cleanup scripts, including a rules.md with your prompt, applying code formatting, etc. Nice to see such a fun use!

// .claude/settings.json

{

"UserPromptSubmit": [

{

"hooks": [

{

"type": "command",

"command": "python3.11 /Claude-Muzak/claude_muzak.py hook start"

}

]

}

],

"Stop": [

{

"hooks": [

{

"type": "command",

"command": "python3.11 /Claude-Muzak/claude_muzak.py hook stop"

}

]

}

]

}Learning Resources & Bookshelf Pages

Very excited to share what aims to be helpful guide for like-hearted creative folks: A bookshelf page and a learning resources page on this site!

My bookshelf has existed on the site for a while, but is now in a fully fleshed out state with all books previously mentioned on the blog in attendance.

I'm most thrilled for my Learning Resources page! Spanning frequent domains on the blog: art, music, software, creativity. There are dozens of entries across books and online material. Some paid, but plenty free as well.

Naturally, both will grow organically over time as I give trial to more material.

I owe a great deal to the folks who have been generous with their books and resources online. Switching into software was a winding road that began with Derek Sivers' book notes. My initial education in software was structured thanks to the thoughtful curation of articles and courses linked through The Odin Project. And the initial map for my art education was borrowed from a generous list by Noah Bradley. The list goes on.

This blog has partly been an attempt to give back as much as I can. With posts spread across several pages, dates, and subjects, it was time to wrap them up with a bow some of my favorites for learning art, music, programming, and living creatively!

If any of these subjects are your medium, I'm hoping there will be some entries that are new to you, and some that will be familiar — casting another vote for the material.

Enjoy!

Gulfer – Heat Wave

Figuring Out Figure Drawing

It's been a couple of years since sharing a peek inside a completed sketchbook.

This one was very targeted in a couple of ways on my part:

I spent a great deal of time with Mike Mattesi's Drawing Force book and web course. I have more to do and learn, but several things started to click during these past few months of focused study!

I pass on the course and books to you with high recommendation. When I first took a stab at the books and the course, I was convinced it was too advanced to be a beginners course. But now I recognize something in the approach that I had done as a teacher myself: planting the seeds for appeal and gesture early (in the case of music: tone and phrasing). It could be saved for later, after the fundamentals are thoroughly set. But why wait? Let compound interest work it's magic.

The style of the Force method is very fluid and alive. It takes wrangling, but it's much more engaging than the more measurement-based approach of pure observational drawing. Like getting at the heart of a piece of music rather than reading notes on the page alone.

Though, I probably spent more time being sure I was seeing the model and staying true to their form. Quite the tricky balance: pushing gesture while capturing essence. I suppose it's not a matter of either/or.

Something that's hard to express through the images alone — it was supremely fun to do! The immediacy, the focus on the energy around expressing the gesture of a pose, and the embodied experience of carving out those rhythms from the figure.

There's simply something to having a sketch on paper sitting on a desk as well. Unmistakably there, holdable in your hands, textured from the material and etchings of the pencil. Am I too romantic about it?

My favorite benefit from spending ample time in a cheap stack of newsprint is how disposable and unprecious it is. Bad drawing? Next page. No Ctrl-Z or glowing screen that urges for polish and perfection. I do love doing digital work. And still, it's nice to take a breather and really let loose on the page.

I still catch myself being surprised that the real skill of art is being able to see. The answer is in plain sight. The muscle that develops is the patience to see more and the pattern matching to capture ideas more quickly.

Onward, to deeper seeing!

Clementi – Sonatina, Op. 36 No. 1 Mvmt. III

A huge milestone in developing proprioception! One of a handful of pieces performed with eyes off the hands and on the sheet music. You can hear me "sounding-out" the next few syllables when a sizable leap is involved. But! All around not too shabby. Progress!

Faber – Jazz Reflections

Diving back into the Faber books to get practice on proprioception!

The Sound Design of Pedestrian Call Buttons

Koichi Sugiyama, 1989, giving advice to aspiring game composers:

Even today, there are still people out there who think that, as long as you have a computer and can use a sequencer, anyone can make game music. And there are a lot of aspiring game music creators with that mentality, too.

And yes, granted, this was to composers of music, and granted, this was 1989...

But! I'm here to demonstrate how even the humble Pedestrian Call Button Makers can hold themselves to higher standards in sound design!

Take a listen to this, dear reader:

UGH! This is a half step moving down. It makes me think of the Straus piece made famous by 2001: A Space Odyssey. (See 0:27 below).

It's alarming, it's a sharp interval. The direction down and the interval add up to a very unpleasant sound. I nearly jumped on the street!!

Now, consider this:

A perfect fourth, ladies and gentlemen. Present in the harmonic series, a symbol of openness, firm, grounded — yet, not entirely resolved. This comfortably leaves you in anticipation for what's next while assuring you that you are, indeed, being taken care of.

Call button designers, take note. One pitch can make all the difference.

Of course, we'd all like to have the luxury of voice in our call buttons. The button in the video below even has an exciting springiness when pressed!

But, alas, not all of the tax dollars can go to such indulgences. So be mindful of your intervals!

Learning Proprioception

For the past year and a half, I've been working on and off on improving an underdeveloped skill on piano. Proprioception is a ten-dollar word for playing without looking at your hands. Broken down, it's the feeling of knowing where your hands are in relationship to the keyboard and knowing the distance you need to move for the next note or chord shape.

If you read only one bit of this as a fellow pianist, take this advice: Start developing it early. It's something that was not emphasized enough when I was taking lessons and class piano, and I certainly wish it were!

Why It Matters

Sight-reading and proprioception are intertwined. They are technically different skills, though. Sight-reading is decoding what is on the page and playing it without prior rehearsal. Proprioception is not sight reading, but it makes sight-reading much easier.

Why does sight-reading matter? Maybe it doesn't to every player. But to me, sight-reading and playing more technical pieces are intertwined. The more you can play without much effort, the better off you are at being able to focus on the new challenge in a denser piece.

Additionally, improvisation requires the level of intimacy with an instrument where phrases are second-nature. Proprioception plays into it.

Lastly — It's just fun! It feels like flying, being able to play without switching your gaze between looking at your hands and the page. Playing the piano is simply more enjoyable this way.

Developing Proprioception

If you're already familiar with playing as I was, there's an unavoidable feeling of really downshifting. New neural pathways were being synthesized. It felt like playing a new instrument once I started taking my eyes off the keys. A rite of passage, a good exercise of the mind, and a hit to the ego, but worth the effort!

All that said, much of the material I worked through started very simple. That's for the best, since an entirely new skill is being learned here to great effect.

Super Sight Reading Secrets by Howard Richman came highly recommended. I dove in here first and would say that this is the "Start Here" for working on proprioception skills. Richman divides exercises between "Keyboard Orientation" (proprioception) and note-recognition skills.

The approach is very gradual and highly tactile. Some teachers would recommend focusing primarily on learning intervals, but Richman takes the long view and encourages you to gain a sense of where each 2/3 note cluster of the ebony keys is located from 0. If presented middle C on the page, the exercises encourage you to find it. Then, removing hands from the keys, doing the same with A2, F5, and so on. Very tedious, progress is slow, but this has been one of the most beneficial exercises in my learning.

There are many more great exercises, thoughtfully ordered. My one note would be that you probably don't need to wait until completing the book before you move on to reading simple music. There are a whole slew of skills that need to stack to read even elementary-grade music, and it's better to start that in tandem with these exercises.

Speaking of, a great companion is Hannah Smith's Progressive Sight Reading Exercises for Piano. This is a book of five-finger pattern 2-3 line pieces. Nice to work through since you're not worried about making leaps across the piano, instead getting a familiarity with feeling different scalar shapes under the fingers. Since there are regular key shifts, this book encourages interval recognition, first in a contained window of five fingers, which then works up to larger leaps after graduating from the book. In actuality, exact-note placement and interval measuring are two lenses that are used in tandem when reading, so it's beneficial to have both developed.

Most recently, and with great jubilation, I've been returning to earlier elementary piano methods. It's time to leave the realm of pure exercise and start applying this to music more regularly. My method series of choice has been the Faber Piano Adventure series, jumping back in at book 3A. Though any method will do, such as the Alfred method.

Progress

I started this in March of 2024, so it's been about a year and a half of gradually working on this in small bursts. Of course, the keyboard orientation exercises took the longest. It's not been until this month that I've felt comfortable enough to work with the elementary method books.

Eventually, though, there was a tipping point. One day, it went from being impossible to — well, possible! Much like a child learning a language, I'm still having to "sound out" (meaning, play really slowly) certain sections, but I can stumble my way into finding where my hands need to go.

When I was first learning piano, playing two hands separately felt like an impossible task. Until it wasn't. After some point, the skill wasn't perfected per se, but I knew that in most pieces I could climb that wall. I'm excited to be reaching a similar point with proprioception and, as a result, sight-reading!

Am I done? Nope! But I do feel that the skill can now develop more naturally as I continue to play. I've broken free from the stratosphere, and it will now be easier to cruise and let the eyes on my finger mature organically. Winston Churchill in Painting as a Pastime encourages "[planting] a garden in which you can sit when digging days are done." Digging days are just about done!

So I'll keep going — enjoying that feeling of soaring whenever my parasail catches a day of good wind!

Post Script: A few bits of very practical advice from Yeargdribble, particularly for anyone picking up Piano as a secondary instrument. Namely:

Debugging React Native App Crashes While Using Expo Camera

I'm spinning up a React Native app that needs to use the device's built-in camera. Not something that is often required in my day-to-day work in web development, but something I figured would be straightforward in 2025!

So I thought!

My jumping off point is Expo's example repo showing how to use expo-camera in your app. Full example file is here. Below, I'll show the relevant code:

export default function App() {

const [uri, setUri] = useState<string | null>(null);

const ref = useRef<CameraView>(null);

const renderPicture = () => {

// . . .

}

const renderCamera = () => {

return (

<CameraView

ref={ref}

mode={mode}

facing={facing}

>

<View style={styles.shutterContainer}>

</View>

</CameraView>

);

};

return (

<View style={styles.container}>

{uri ? renderPicture() : renderCamera()}

</View>

);

}Our app has two views: The camera and the picture display. Once you take a photo from the camera, the picture display shows the photo. After closing that, you return to the camera.

I'm starting with iOS, since that's what I use. Camera functionality is not available on the device simulator on Mac, so I'm reaching for my own iPhone SE 2.

After playing around with the example in Expo Go, the app crashes.

At first, I didn't think much of it. It could have been a number of small things! Perhaps the code needs refactoring, the render functions broken out to components, the state management being optimized, the camera ref being converted to state that's cleared on unmount.

Needless to say, dear reader, none of that did the trick.

Below, I'll outline the methods I tried out. If you're experiencing the same issue, one may work for you. At the end, we'll discover a big ol' twist as far as how I resolved it.

Preview

I began to think it was an issue with the Camera preview. Perhaps, when leaving the page, the preview was running in the background, and returning to it caused the crash.

The camera instance has methods for pausing and resuming the preview. I chose to handle this in a useEffect: resuming on component mount and pausing on unmounting.

useEffect(() => {

ref.current?.resumePreview();

return () => {

ref.current?.pausePreview();

}

}, [ref.current]);Alas, no luck.

Focused

As per the expo-camera docs, it's important that only one instance of the camera be available at any given time. This apparently can be tricky with multi-screened apps. Not all components may fully unmount, say, when you open up a modal, for example.

The way to handle this is to render your camera behind a check for if the page is focused. Thankfully, there's a hook available for this:

import { useIsFocused } from '@react-navigation/native';

export default function Index() {

const isFocused = useIsFocused();

if (isFocused) return <Camera />;

}No dice in my case. Crashes continued.

Reloading The App

I'll truncate the rest of the story to say I tried several hacky solutions. I was starting to get desperate!

I'd narrowed it down to being related to the expo-camera component and remounting it after an initial load. However, it was never a problem on first load. So what if I could reload the app?

Thankfully, there's a programmatic way to do it. So, after sending a picture, I set the app to reload.

export default function ImagePreview({ uri }: ImagePreviewProps) {

const handleSend = async () => {

setSending(true);

setTimeout(() => {

setSending(false);

setSent(true);

setTimeout(() => {

if (Platform.OS === 'ios') {

console.log('iOS detected');

reloadAppAsync();

} else {

router.back();

}

}, 2000);

}, 4000);

};

}You'll notice I'm only doing this on iOS. By this point, I discovered the issue was not present in my Android simulator.

It's an ugly solution. I couldn't wrap my mind around how I was getting such spotty performance here. Though the Android success started to get me thinking about another angle to take.

Testing Multiple Devices

As mentioned, my tests were on an iPhone SE 2. What I soon realized is that I was only testing on that phone.

I picked up an iPad and ran my app. I reverted back to the original example code. After some testing, I didn't experience any crashes.

A bitter-sweet victory! Relieved that the problem was device-specific, and stunned that I spent so much time trying to handle what was largely a non-issue on most devices!

Device Specific Code

Thankfully, from here on out, the solution was simple. I already had a hack that seemed to mitigate the issue on my iPhone. And I have a couple of examples of the original code working seamlessly.

The solution then was to do what I'm sure takes up a major part of a React Native app: device-specific code!

I'll have to gather results on more devices as I continue. But, it seemed a safe bet that there was an issue with my phone's OS version. With my phone on version 16 and iPad on 17, I decided to use the reload hack only on iOS version 16 devices.

const isMajor16 = (ver: string | null) => ver && /^16\./.test(ver);

// . . .

if (Platform.OS === 'ios' && isMajor16(osVersion)) {

console.log('iOS 16 detected');

reloadAppAsync();

} else {

router.back();

}👋

In the world of web development, we're fortunate to have fairly unified environments. Developing across mobile environments is a bit messier. On top of differences between OS's, version differences caught me off guard.

So, if you're jumping into mobile dev, have multiple devices handy, friends!

Resting

Art & Science from Art & Fear

A section from the book Art & Fear by David Bayles & Ted Orland. Highlighting how both practices are in search of universal Truths:

It is an article of faith, among artists and scientists alike, that at some deep level their disciplines share a common ground. What science bears witness to experimentally, art has always known intuitively — that there is an innate rightness to the recurring forms of nature. Science does not set out to prove the existence of parabolas or sine curves or pi, yet wherever phenomena are observed, there they are. Art does not weigh mathematically the outcome of the brushstroke, yet whenever artworks are made, archetypal forms appear.

A significant departure from the two, however, is the lived experience vs the theoretical:

"The main thing to keep in mind", as Douglas Hofstadter noted, "is that science is about classes of events, not particular instances." Art is just the opposite. Art deals in any one particular rock, with its welcome vagaries, its peculiarities of shape, its unevenness, its noise. The truths of life as we experience them — and as art expresses them — include random and distracting influences as essential parts of their nature. Theoretical rocks are the province of science; particular rocks are the province of art."

Is there significance to those unique peculiarities? The authors make the case for it:

The world we see today is the legacy of people noticing the world and commenting on it in forms that have been preserved. Of course it's difficult to imagine that horses had no shape before someone painted their shape on the cave walls, but it is not difficult to see the world became a subtly larger, richer, more complex and meaningful place as a result.