Chris Padilla/Blog

My passion project! Posts spanning music, art, software, books, and more. Equal parts journal, sketchbook, mixtape, dev diary, and commonplace book.

- Initial function start, get a list of pages to crawl.

- Sequentially crawl those pages. (separate lambda function called sequentially)

- After page crawl, send an update on the status of the crawl and update the DB with results.

- Call a script with github-script

- From said script, scan for the latest post.

- Grab the relevant content (an image or video link)

- Integrate with my messaging system of choice, either:

- Twilio to send a text

- Amazon Simple Email Service

Coordinating Multiple Serverless Functions on AWS Lambda

Sharing a bit of initial research for a serverless project I'm working on.

I've been wrestling this week with a challenge to coordinate a cron job on AWS Lambda. The single script running on Lambda is ideal. There's no server overhead, the service is isolated and easy to debug, and it's cost effective. The challenge, though, is how to scale the process when the run time increases.

Lambda's runtime limit at this moment is 15 minutes. Fairly generous, but it is still a limiter. My process will involve web scraping, which if done sequentially, could easily eat those 15 minutes if I have several processes to run.

The process looks something like this so far:

Simple when it's 3 or 5 pages to crawl for a minute each. But an issue when that scales up. Not to mention the inefficiency of waiting for all processes to end before sending results from the crawl.

This would be a great opportunity to lean on the power of the microservice structure by switching to concurrent tasks. The crawls are already able to be sequentially called, the change would be figuring out how to send the notification after the crawl completes.

To do this, each of those steps above can be broken up into their own separate lambda functions.

Once they're divided into their own serverless functions, the challenge is too coordinate them.

Self Orchestration

One option here would be to adjust my functions to pass state between functions. Above, the 1st lambda would grab the list of pages, and fire off all instances of the 2nd lambda for each page. The crawler could receive an option to notify and update the db.

It's a fine use case for it! With only three steps, it wouldn't be overly complicated.

To call a lambda function asynchronously, it simply needs to be marked as an "Event" type.

import boto3

lambda_client = boto3.client('lambda', region_name='us-east-2')

page = { ... }

lambda_client.invoke(

FunctionName=f'api-crawler',

InvocationType="Event",

Payload=json.dumps(page=page)

)Step Functions

Say it were more complicated, though! 3 more steps, or needing to handle fail conditions!

Another option I explored was using Step Functions and a state machine approach. AWS allows for the ability to orchestrate multiple lambda functions in a variety of patterns such as Chaining, branching, and parallelism. "Dynamic parallelism" is a patern that would suit my case here. Though, I may not necessarily need the primary benefit of shared and persistent state.

The Plan

For this use case, I'm leaning towards the self orchestration. The level of state being passed is not overly complex: A list of pages from step 1 to 2, and then a result of success or failure from step 2 to 3. The process has resources in place to log errors at each step, and there's no need to correct at any part of the step.

Next step is the implementation. To be continued!

Time to Boogie Woogie!

Walking that bass! Trying out playing without looking at my hands as well.

Followed this great video tutorial for the tune

Aang

New Album — Flowers 🌸

Incase you missed it! Celebrating the arrival of spring! I've always loved how these two flowers speckle the hills and fields this time of year.

Purchase on 🤘 Bandcamp and Listen on 🙉 Spotify or any of your favorite streaming services!

SSL Certifications in Python on Mac

Busy week, but I have a quick edge case to share:

We've upgraded to a newer version of Python for our microservices at work. While making the transition, I bumped into an error sending http requests through urllib3:

SSL: CERTIFICATE_VERIFY_FAILEDI've come across this issue before, having to manually add certs. The solution involved low level work and was gnarly to handle! Thankfully, though, with Python 3.6 and higher, the solution is more straightforward.

It's largely outlined in this Stack Overflow post by Craig Glennie. The gist is that on Mac, you actually have to run a post install script located in your Applications/Python folder.

If you follow along with Craig's post, you'll find that the documentation for it is even there in the Python README. Always good to read the manual!

Satchmo

Lazy Sunday Improv

Pup at Twilight

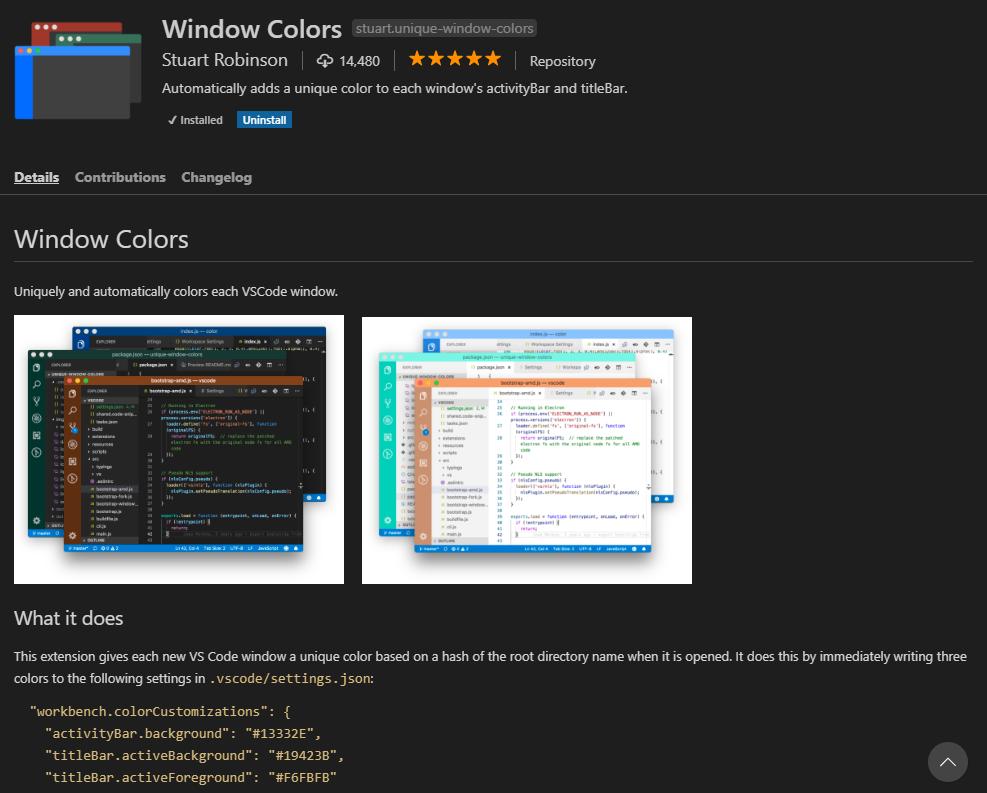

Customizing Title Bar Colors in VS Code

We're doing a lot of migration from one repo to another at work. And it's easy to mix up which-window-is-which when looking at two files that are so similar!

Enter custom Title Bar Colors! Not only does doing this look cool, it's actually incredibly practical!

I first came across this in Wes Bos' Advanced React course, and it's sucinclty covered on Zachary Minner's blog: How to set title bar color in VS Code per project. So I'll let you link-hop over there!

If you don't want to pick your colors, looks like there's even a VS Code plugin that will do this automatically for you! (Thank you Stack Overflow!)

Blue Bossa

The Boy and the Heron

Regex Capture Groups in Node

I've been writing some regex for the blog. My blog is in markdown, so there's a fair amount of parsing I'm doing to get the data I need.

But it took some figuring out to understand how I could get my capture group through regex. Execute regex with single line strings wasn't a problem, but passing in a multiline markdown file proved challenging.

So here's a quick reference for using Regex in Node:

RegExp Class

new RegExp('\[([^\n\]]+)\]', 'gi').exec('[a][b]')

// ['a']Returns only the capture groups. Oddly, there is a groups attribute if you log in a Chrome browser, but it's undefined in the above example.

The issue here comes with multiline string. If my match were down a few lines, I would get no result.

You would think to flip on the global flag, but trouble arises. More on that soon.

RegExp Literal

/\[(a)\]/g.exec('[a][b]')

// ["[a]", "a"]Returns the full match first, then the grouped result. Different from the class!

I was curious and checked it was an instance of the RegExp class:

/fdsf/ instanceof RegExp

// trueAnd so it is! Perhaps it inherits properties, but changes some method implementations...

String Match

'[a][b]'.match(/\[(a)\]/g)

// ["[a]"]You can also call regex on a string directly, but you'll only get the full match. No capture group isolation.

Again, problems here when it comes to multiline strings and passing the global flag.

The Global Option

The Global option interferes with the result. For example: Passing a global flag to the RegExp class will actually not allow the search to run properly.

The only working method I've found for multi line regex search with capture groups is using the Regexp literal.

My working example:

const artUrlRegex = /[.|\n]]*\!\[.*\]\((.*)\)/;

const urls = artUrlRegex.exec(postMarkDown);

if(urls) {

const imageUrl = urls[1];

. . .

}Surprisingly complicated! Hope this helps direct any of your future regex use.

Fly Me To The Moon

Walking the Bass, flying to the moon 🌙

Oatchi

Triggering Notifications through Github Actions

My Mom and Dad are not on RSS (surprising, I know!) Nor are they on Instagram or Twitter or anywhere! But, naturally, they want to stay in the loop with music and art!

I've done a bit of digging to see how I could set up a notification system. Here's what I've got:

This blog is updated through pushing markdown files to the GitHub repo. That triggers the build over on Vercel where I'm hosting things. So, the push is the starting point. I can:

The config for github scripts is very straightforward:

name: Hey Mom

on: [push]

jobs:

hey-mom:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

- uses: actions/github-script@v7

with:

script: |

const script = require('./.github/scripts/heyMom.js')

console.log(script({github, context}))The one concern I have here is external dependencies. From my preliminary research, it's best to keep the GitHub Action light without any dependencies. Mostly, I want it to find the content quickly, and send it off so the website can finish up the deploy cycle.

This would be a great case for passing that off to AWS Lambda. The lambda can take in the link and message body, load in dependencies for integrating with the service, and send it off from there.

Though, as I write this now, I'm forgetting that Vercel, of course, is actually handling the build CI. This GitHub action would be separate from that process.

Well, more to research! No code ready for this just yet, but we'll see how this all goes. Maybe the first text my folks get will be the blog post saying how I developed this. 🙂